Led Zeppelin was the first (and maybe still only) band to be formed with the express intent of becoming the biggest rock stars in the world that then actually succeeded in that goal. Everything about them was huge: their talent, their sound, their ambitions and egos and appetites. In the 1970s, they helped shape every fantasy of hard-rock excess: groupies, fast cars, private jets, stadiums, drugs, trashed hotels, rumors of the occult, you name it. They sold tens of millions of records and unfathomable numbers of concert tickets, briefly managed to make being obsessed with hobbits appear sexy, and became an aspirational blueprint for countless hard rock bands to follow, some successful, most less so, all inferior to the original.

But there was one thing Led Zeppelin craved that always eluded them, even at their greatest heights: They wanted to be taken seriously. The extent to which rock critics hated the band has always been a bit overstated in the telling—often by Zeppelin themselves, who were obsessive readers of their own press—but there’s no doubt that there was a certain, high-profile cadre of detractors who saw the band as a crass, cynical, and distressingly lucrative nail in the coffin of the utopian rock-’n’-roll dreams of the 1960s. (Led Zeppelin’s self-titled debut actually came out in January 1969, seven months before Woodstock, but imagining the band at that festival is a little like imagining Godzilla showing up in Casablanca.) And the group’s pomp and pretentiousness always lent itself to ridicule: 1984’s This Is Spinal Tap, the greatest satire of rock music ever made, wasn’t explicitly about Led Zeppelin, but you didn’t have to squint to see the resemblance.

Becoming Led Zeppelin, filmmaker Bernard MacMahon’s new documentary about the band, certainly succeeds at taking Led Zeppelin seriously, in ways that might disappoint some viewers but that I found both compelling and refreshing. Becoming Led Zeppelin doesn’t hide that it’s an authorized biopic—all three surviving members of the band effectively serve as the movie’s onscreen narrators, beside recordings from a previously unreleased interview with late drummer John Bonham—but the film is so fastidious and detail-oriented that it never feels like hagiography. It’s a nice reminder that before they were gods, these guys were unabashed music nerds, and the film is both tribute to and product of that nerdery.

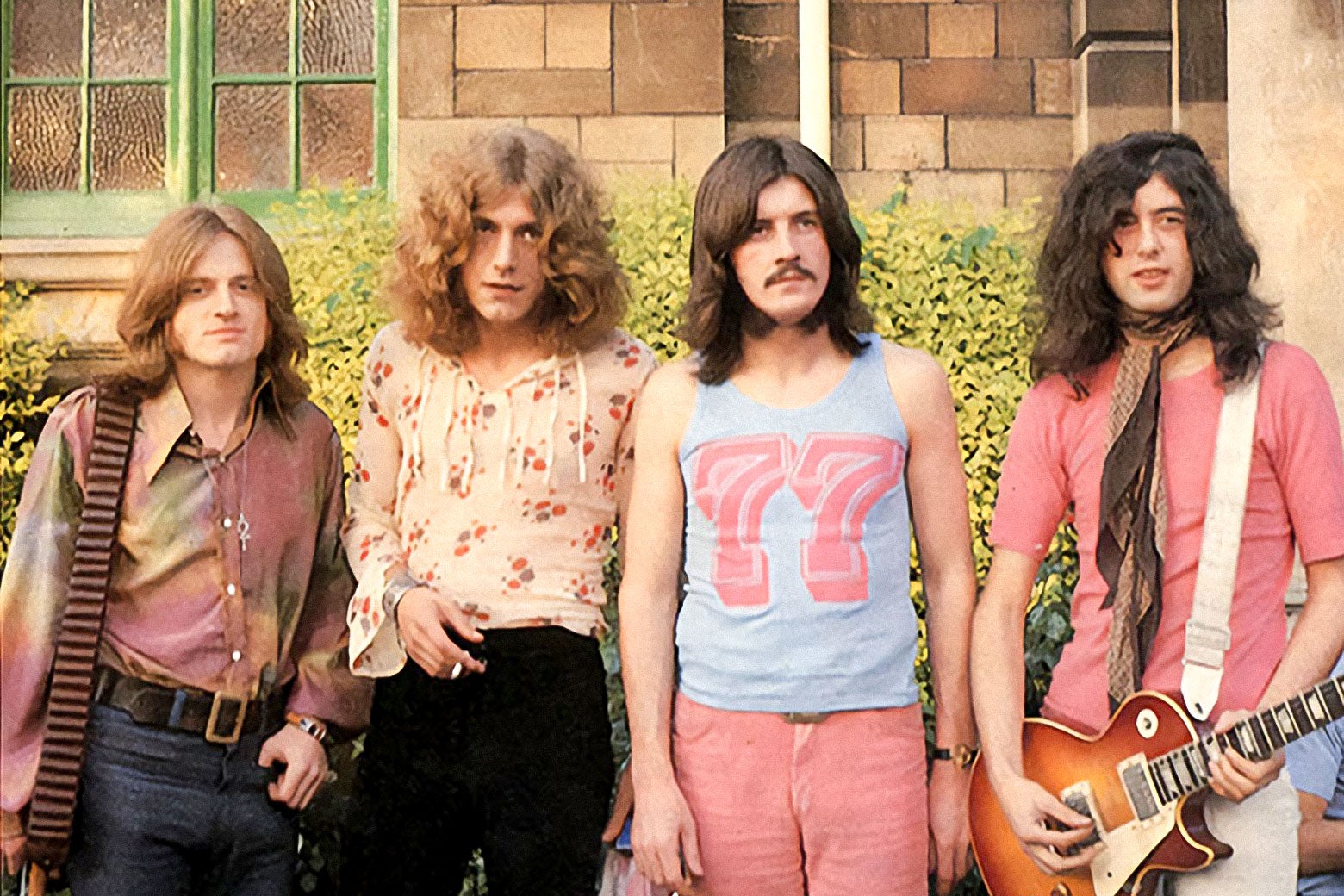

The foursome of guitarist Jimmy Page, singer Robert Plant, bassist and multi-instrumentalist John Paul Jones, and drummer Bonham were a mercenary project from the beginning. Page and Jones were already two of the top session musicians in England, while Plant and Bonzo had gained some renown performing together in the psychedelic blues outfit Band of Joy. Fresh off a stint in the recently defunct Yardbirds, Page yearned to break out of his studio-rat reputation and break into rock stardom. After assembling the band and embarking on a now-legendary tour of Scandinavia (during which they were still billed as the Yardbirds), Page made the remarkable decision to fund the sessions for Led Zeppelin’s self-titled debut himself. After the recording and mixing were complete, Page brought it to Atlantic Records, who signed the group after agreeing to Page’s insistence that the label would leave the finished LP untouched. The rest, as they say, is history.

Becoming Led Zeppelin’s title is rather literal: The film is really an origin story rather than a conventional history-of-the-band documentary. The documentary ends with the release of Led Zeppelin II in late 1969, meaning we don’t even make it into the 1970s, a decade whose musical legacy Zeppelin played an outsize role in helping define. You won’t hear a note of “Immigrant Song” or “Stairway to Heaven” or “Kashmir” here (though what you do hear sounds magnificent in the film’s IMAX release), nor will you be treated to much in the way of sex-drugs-and-rock-’n’-roll decadence, to say nothing of mud sharks and other apocrypha. (For those disappointed by this, Hammer of the Gods is still very much in print.)

But there are still great stories to be found here: how Jones bought his first bass at 14, with money he’d saved from his gig as a church organist and choirmaster; how Plant’s parents stopped speaking to him after he abandoned a future career as an accountant to pursue music (they later patched things up); how Page’s encounters with FM radio while touring the U.S.

with the Yardbirds helped convince him that album-oriented rock was the future, hence his refusal to allow Atlantic to issue a single from Led Zeppelin. Some may find the generous helping of time spent on Page and Jones’ work on mid-1960s classics like Shirley Bassey’s “Goldfinger” and Donovan’s “Sunshine Superman” digressive, but I found it weirdly thrilling. (Two future members of Led Zeppelin played on Lulu’s 1967 schmaltz-pop masterpiece “To Sir With Love!”)

If the film’s focus on the band’s beginnings makes for a rather un-flashy story, one gets the suspicion that Plant, Page, and Jones are genuinely far more enthusiastic to reminisce on their musical salad days than they are their more storied and salacious imperial period. All three men are engaging onscreen presences: funny, insightful, and down-to-earth. Jones, in particular, who’s long been the most low-profile and reticent of the group, is a thoroughly delightful interview subject, puckish and self-effacing, somehow still boyish at nearly 80 years old.

Particularly moving are moments when the filmmakers play portions of the unreleased Bonham interview to Page, Plant, and Jones. They’ve presumably never heard it either, and all three react with disarming amounts of affection. The aloofness with which Zeppelin conducted themselves in public—an affectation that made the interpersonal dynamics of the foursome more inscrutable than, say, the Beatles or the Rolling Stones—can make it easy to lose sight of the enormous impact these four men had on each other’s lives, and the intense if complicated bonds that still exist between them. (Page, Plant, and Jones never appear onscreen together in the film, but there’s no hint of lingering tension or antipathy in their interviews.)

If anything, the film’s most admirable quality—the deliberate modesty of its scope and tone—is also its main weakness. If you’re not already aware of Led Zeppelin’s significance in musical history, you won’t learn much about that here. So many music docs are so eager to print the legend that it’s refreshing to watch one that so resolutely declines to do that, but at the same time, this is a band whose legend was unusually influential. I can understand why a septuagenarian Robert Plant isn’t dying to talk about his status as sex god to a generation of horny teenagers, and I can certainly understand Jimmy Page not wanting to talk about his personal life in the 1970s. But these are important parts of the Led Zeppelin story, too. (I knew the “If I played guitar I’d be Jimmy Page/ The girlies I like are underage” line from the Beastie Boys’ “The New Style” before I even knew who Page was.)

One of the flaws inherent to the ever-burgeoning genre of artist-sanctioned music documentaries is the fact that, in reality, artists don’t really get to decide what makes them interesting to the world. Most of the time this manifests itself in an inflated insistence on importance and a boring paint-by-numbers triumphalism—propaganda for celebrities, by celebrities. Becoming Led Zeppelin avoids this but still very much feels like a story the band wants to tell, rather than the story people should know. Here’s hoping that the lads take a page from their main man J.R.R. Tolkien and blow it out into a trilogy—I’d watch a sequel called Being Led Zeppelin in a heartbeat.