“John was always commenting on useful things that the rest of his bandmates hadn’t talked about.

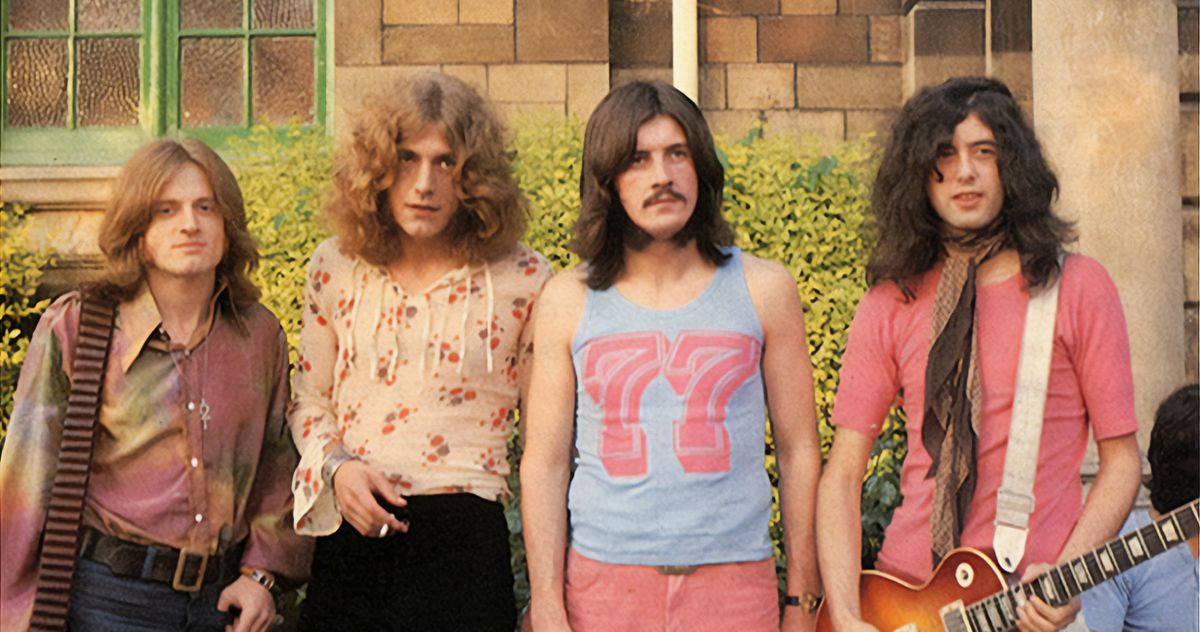

Photo: Paradise Pictures/Sony Pictures Classics

Robert Plant never thought a documentary about Led Zeppelin would be possible. Not, say, for reasons of vanity or hesitancy to discuss the past, as he indulged this very outlet two years ago. The hard truth was John Bonham, the band’s late virtuosic drummer, barely offered himself up for interviews when he was alive, a practice that was often mirrored by the rest of the group until they broke up in 1980. How could you tell the full story of Zeppelin without Bonzo’s insights, or any new insights at all, for that matter? “Robert said to me, ‘I don’t think you can make this film. We didn’t do interviews. We didn’t do television. There’s just not enough,’” director Bernard MacMahon recalls.

Yet here we are, with new blueprints for a house of the holy. Plant, Jimmy Page, and John Paul Jones all eventually agreed to participate in Becoming Led Zeppelin (out now in Imax), which traces the band’s origins until Led Zeppelin II skyrocketed in popularity in early 1970. Plant and Page were impressed by 2017’s American Epic, MacMahon’s documentary about the history of roots music, which encouraged them to put their trust in the project and also convince Jones of its merits. The trio sat for separate interviews — albeit a bit sanitized — to reveal the brotherhood of those early years and the unlikely way they came together. (If you were hoping for confirmation about the mud-shark incident, you’re going to leave disappointed.) But MacMahon and his producing partner, Allison McGourty, knew that the documentary’s release hinged on the discovery of previously unheard Bonham material. And it was going to be a mad quest to find it.

“We were searching and searching and searching,” MacMahon says. “It was imperative to have his voice.” The duo got a decent start by fielding a tape from a British music journalist of the era who was lucky to secure time with Page and Bonham, but the sound quality was abysmal. “It was a ton of noise that made it sound like an espionage film,” he says. MacMahon then consulted the man behind Led Zeppelin’s website, who, in his informal archivist role, made a point to collect “every single thing” he found in relation to the band. “He shared with us this bootleg recording of John and Robert talking to an Australian journalist,” he explains. “The recording wasn’t good enough for us to use. But I could tell that it was three or four generations copied. We sent it to a lot of people we knew in Australia and hoped for the best.”

The best actually did happen. One of their sources found someone who recognized the voice of the journalist Graeme Berry, who worked for the radio station Sydney 2SM. The interview was believed to have been conducted in 1971. “The great thing about it was John is completely in the moment. It’s super fresh and it’s got this energy,” MacMahon says. “He’s talking about stuff that happened, some of which the band didn’t comment on in their other interviews. The interviewer is basically introducing Led Zeppelin to Australia before their first tour there. John was being asked, ‘How did you learn to play drums? Who did you look up to?’ Simple but productive questions.”

Sydney 2SM no longer stored tape recordings — a pristine original tape was still crucial — so they instead directed MacMahon and McGourty to the University of Canberra, which took over the bulk of the station’s archives. “The university looked but they said they didn’t have it,” MacMahon recalls. “So I asked them, How many uncatalogued tapes do you have? They said thousands.” Faith struck again: He had previously worked with the university on American Epic, forming a good professional relationship that could be parlayed into a favor. “I asked, ‘Hey, would you mind looking?’ And they said okay. A few months later I got a phone call around midnight from a person who said, ‘Open your email,’” MacMahon recalls. “And there was a perfect recording of John speaking. They had found this tape in an unmarked box that read ‘Slade,’ another British band. They were so diligent going through everything, threading these reels up, and listening to them all.”

The university sent the tape to MacMahon and McGourty’s facility so they could copy the best possible sound off it. All together, Becoming Led Zeppelin secured about 90 minutes of never-heard Bonham interviews — including two additional radio spots that were unearthed shortly thereafter. Bonham’s sister, Deborah, also provided the team with home movies from their childhood, which captured endearing footage of Baby Bonzo playing his first-ever drum kit with just a snare and cymbal. This material guided the production into what became the beating heart of the final cut. “The tapes have John talking about his bandmates and what he feels about them,” MacMahon says. “He was always commenting on useful things that the rest of his bandmates hadn’t talked about. He was the one who talked about how nobody wanted to book the band in their home country. And at the end of the film, he lets the viewer know that they barely know each other. He says, ‘I’m just getting to know them. I like John, Jimmy is really shy, and I know Robert a bit better.’ These are relative strangers to each other even by the end of their first year. It’s all about the music.”